The unveiling of the new Dr. Martin Luther King's memorial designed and created by sculptor Lei Yixin was a major event in Washington D.C. and it had generated much discussions and even debates. The debates took place largely when the project announced the chosen sculptor, largely due to his Chinese origin. The the debut of the sculpture, the discussion now shifted to the representation of Dr. King, the merit of the sculpture as memorial and artistic achievement. New York Times published a long article on this project and the highlights are as follow:

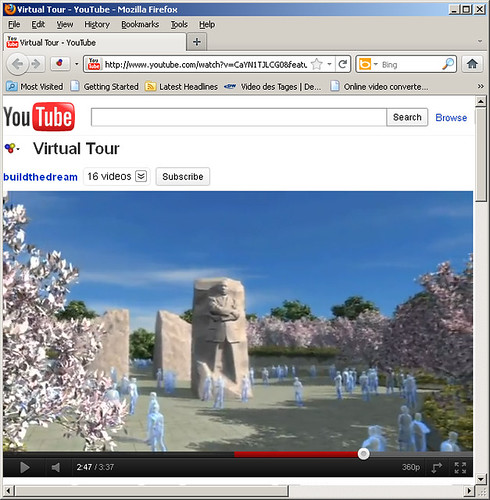

The still photo above gives us a close up of that face hoovering in the clouds which the video below from the official website give us some idea of what they want us to see. I think some shots at below moments are very representative: 2:24, 2:47 and 3:18:

That figure is the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and this Sunday, when his four-acre, $120 million memorial on the edge of the Tidal Basin is to be officially dedicated, it will be adjacent to Franklin D. Roosevelt’s, across the water from Thomas Jefferson’s, and along an axis leading from that founding father directly to Abraham Lincoln’s. There are few figures in American history with similar credentials who would have even a remotely comparable claim for national remembrance on the Washington Mall.

Perhaps, though, it was the presence of such company that led to the kind of memorial that now exists. There is always an element of kitsch in monumental memorials, a built-in grandiosity that exaggerates the physical and spiritual statures of their human subjects.

So it should be no surprise that something similar happens to Dr. King. But his statue goes even further. Those of Jefferson and Lincoln are a mere 19 feet tall; Dr. King looms 30 feet up, staring over the Tidal Basin. And he isn’t decorously posed in a classical structure; he isn’t contained in an ordered space with Greek or Roman allusions. His form emerges halfway out of an enormous mound of granite so heavy that 50-foot piles had to be driven into the ground to provide support.

We don’t even see his feet. He is embedded in the rock like something not yet fully born, suited and stern, rising from its roughly chiseled surface. His face is uncompromising, determined, his eyes fixed in the distance, not far from where Jefferson stands across the water. But kitsch here strains at the limits of resemblance: Is this the Dr. King of the “I Have a Dream” speech? Or the writer of the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech?

But do these mounds of granite, which are given an almost artificial appearance with their sketchy, cartoonish contours — do they evoke anything at all like a “mountain of despair”? And the unattractive slice supposedly pushed into the center of the memorial: is that really a “stone of hope”? Certainly not, judging from the expression on Dr. King’s face.

The metaphor is not one of Dr. King’s best, anyway, but to center an entire memorial on it, and then to do so in a way that makes no real sense, is baffling. Moreover, the original context of the line from the speech is quite different. Dr. King, after the demonstration in Washington, was going back to the South, his faith intact.

And the mound’s isolation from any other tall objects, its enormity and Dr. King’s posture all conspire to make him seem an authoritarian figure, emerging full-grown from the rock’s chiseled surface, at one with the ancient forces of nature, seeming to claim their authority as his. You don’t come here to commune with him, let alone to attend to the ideas the memorial’s Web site insists are latent here: “democracy, justice, hope and love.” You come to tilt your head back and follow; he, clearly, has his mind elsewhere.

Thus we can see much more vividly, almost in situ. The unrealistically polished folds of his impeccably suit, his haughtily crossed arms, his stern facial expression all conspired to make him as authoritative and aloof as possible, rather than a fiery and compassionate man who has a deep connection to the time, the people and their sufferings. To me, it invokes the unpalatable feelings of encountering those always-correct Communist leaders on high horses, such as the Stalin statue below:

I think to make the appropriate tribute to Dr. King, a statue in the style of Rodin's "The Burghers of Calais" would be much more proper:

The Burghers of Calais, Auguste Rodin, Stanford University

Or the Memorial in Berlin to all victims of war and violence by Käthe Kollwitz, which was just as stylized and sleek bu full of emotion and compassion:

This Dr. Martin Luther King's statue by Mr. Lei - with a startlingly similar facial features to the artist and a grandiose profile to that of an Egyptian deity - failed to measure up to the essence of Dr. King and what he represented for and is not a successful addition to the capital where he delivered his important speech, I Have a Dream, surrounded by people he had been fighting for:

The greatness of Dr. King is not to be judged by the size of his pedestal.

No comments:

Post a Comment