Though I have always been drawn to Northern and Central European artists, such as those from Germany and Netherlands, before my recent trip to Vienna, Austrian artists, beside

Oska Kokoschka, hadn't made much impression on me, though I was not aware of other leading figures, such as

Gustav Klimt (1862-1918) and

Egon Schiele (1890-1918).

Of these two, I was more familiar with Klimt, largely due to the broadly-reported lawsuit over his painting,

Adele Bloch-Bauer I, which eventually was transferred from Belvedere, Austria to the heir to its original Jewish owner, then was sold to

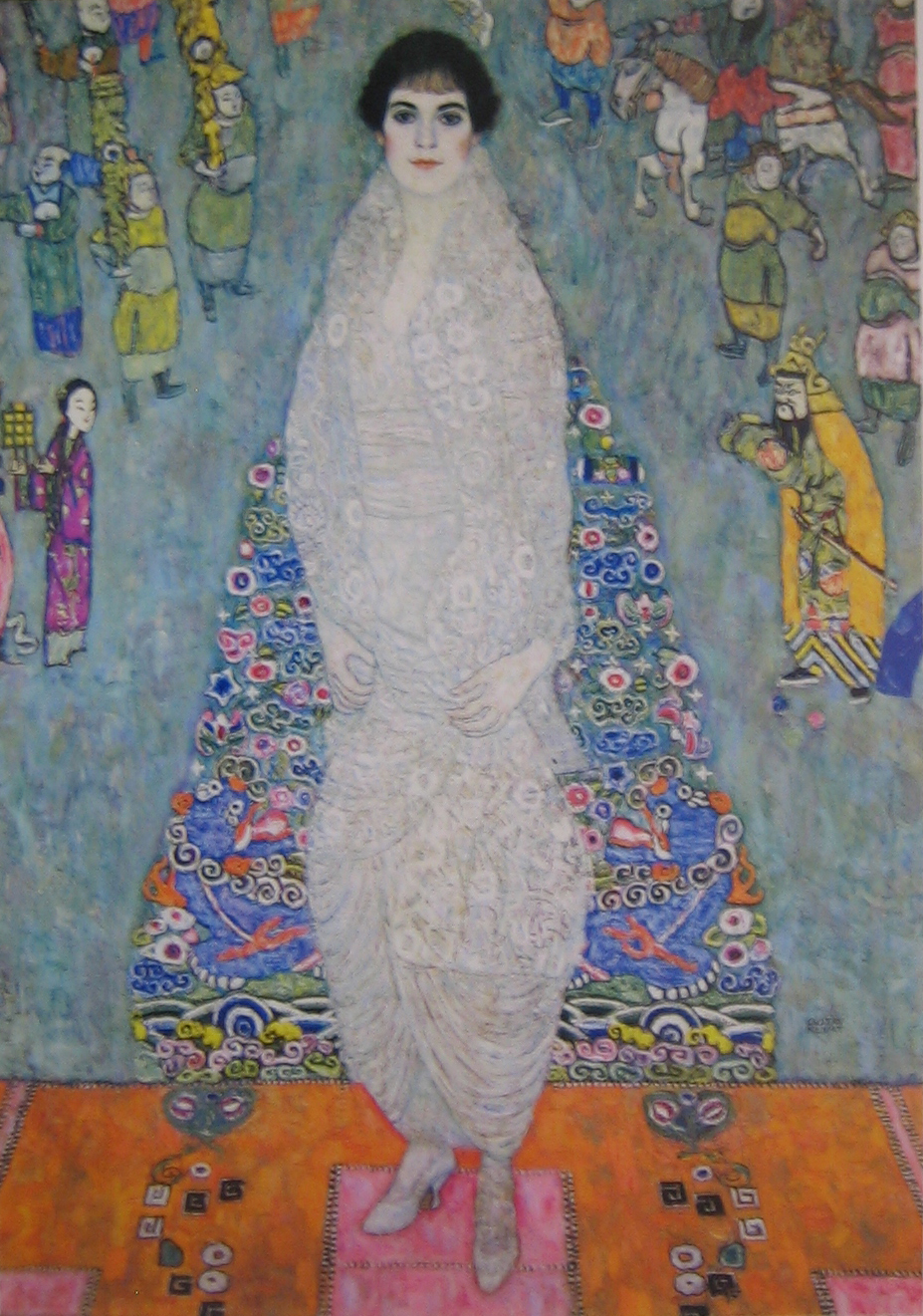

Neue Galerie, New York, and there I saw the painting in 2010, along with Klimt's

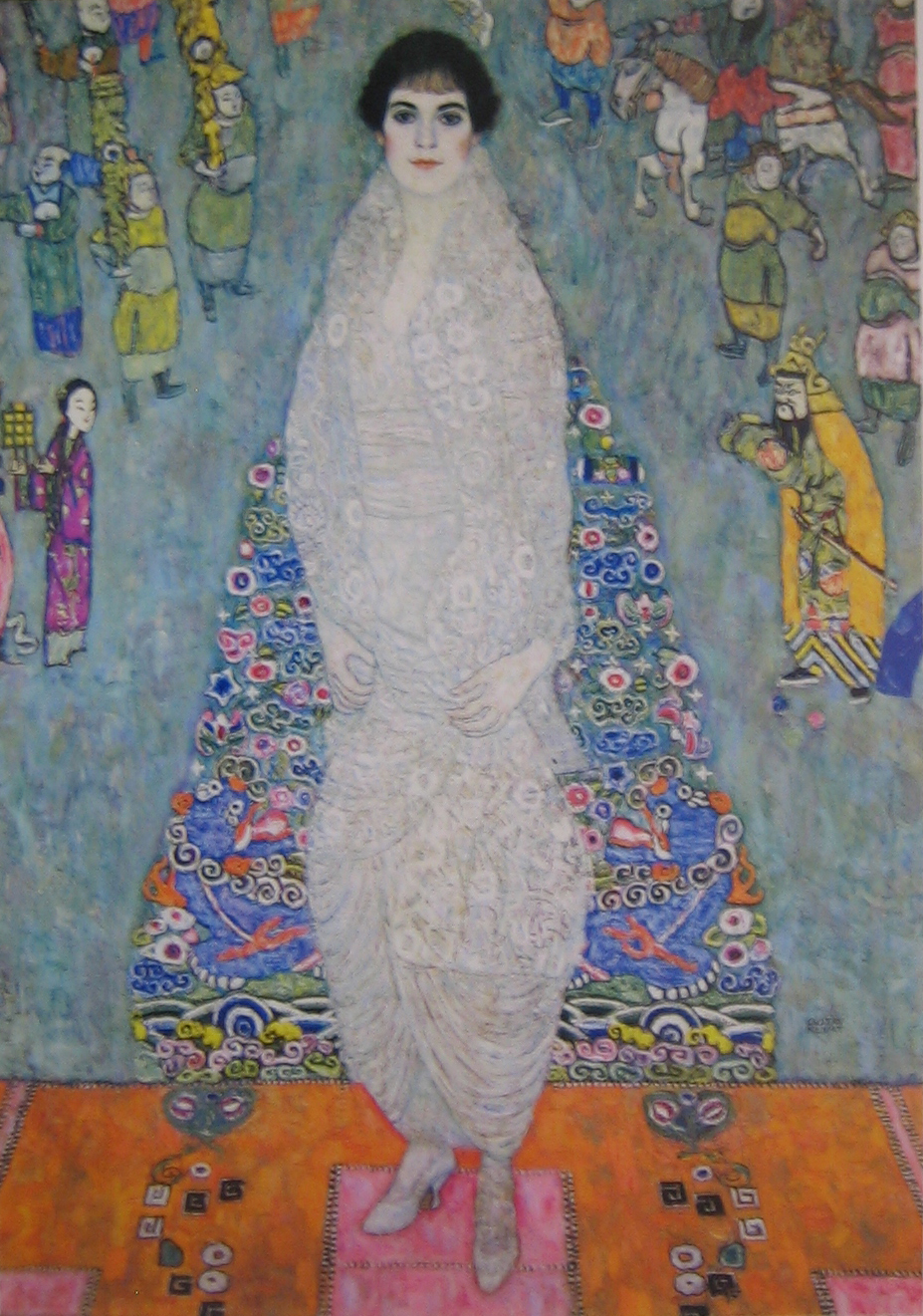

Bildnes Baronin Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt (Portrait of Baroness Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt). During the same trip, in

New York MOMA, I also saw Klimt's Hope, II. Egon Schiele was fuzzier to me.

Adele Bloch-Bauer I, Gustav Klimt, 1907, Neue Galerie New York

Adele Bloch-Bauer I, Gustav Klimt, 1907, Neue Galerie New York

Bildnes Baronin Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt (Portrait of Baroness Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt), Gustav Klimt, c. 1914, Neue Galerie New York

Bildnes Baronin Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt (Portrait of Baroness Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt), Gustav Klimt, c. 1914, Neue Galerie New York

Hope, II, 1907-08, Gustav Klimt, Museum of Modern Art (MOMA), New York City

Hope, II, 1907-08, Gustav Klimt, Museum of Modern Art (MOMA), New York City

In October, I re-visited Vienna, Austria, where the 150th anniversary of Gustav Klimt was being celebrated by practically every important art museum, therefore my survey of his oeuvre became more comprehensive and I had much better understanding of Klimt.

In the meanwhile, the new museums I visited during that second trip to Vienna, mostly concentrating on Austrian art, brought me to the presence of another great Austrian artist, Egon Schiele and he instantaneously became one of my favorite artists.

Both Klimt and Schiele represented perfectly their time and place, with the older Klimt, the epitome of eroticism and decadence, the excess of fin de siècle, thoroughly bourgeois, and the younger Schiele, the comprehensive fear of the end of the century and the clear and present doom to come, despite his occasional Tiffany lamp styled, innocent enough landscapes and townscapes.

Since Klimt was the of the founding members and president of the

Wiener Sezession (

Vienna Secession) in 1897, it is fitting to start my discussion from a trip to

Secession Building (

Wiener Secessionsgebäude).

Secession (Wiener Secessionsgebäude), Wien

Secession (Wiener Secessionsgebäude), Wien

The center piece of Klimt celebration in this rather modest museum was the

Beethoven Frieze, loaned from Upper Belvedere, after Richard Wagner's interpretation of Ludwig van Beethoven's Ninth Symphony, with an overall length of 34.14 m (long walls 13.92 m each, front wall 6.30 m), and height of 2.15

- 2.00 m. There was a fascinating video of the restoration process of this rather delicate, and "temporary" work. There was a replica of a section of it for viewers to exam very closely. For the real thing, one could see it in reasonably close range, on raised platform, mounted on top of a specially built room to its specific dimensions, covering all four sides of the wall. The dominant theme was love or lust and the overwhelming color was gold. This series was heavy with symbols yet I felt it was a bit underwhelmed, despite its visual dazzle.

Beethoven Frieze restoration video, Secession, Wien

Beethoven Frieze restoration video, Secession, Wien

Beethoven Frieze restoration video, Secession, Wien

Beethoven Frieze restoration video, Secession, Wien

Beethoven Frieze copy, Secession, Wien

Beethoven Frieze copy, Secession, Wien

For more permanent murals by Klimt, one should go to Burgtheater and Kunsthistorisches Museum. I did spent a night at Burgtheater for a play by Herinch von Kleist -

Der Prinz von Homburg, but we missed the entrance to the grand staircase adored with Klimt's murals before the show and it was closed afterward. No intermission to exploit. We were able, however, to see some of his drawings on the wall, just outside the auditorium. Without the glittery colors he loved to employ, one could appreciate more of his draftsmanship but they didn't have the hallmarks of a Klimt and definitely was not as satisfying.

Burgtheater, Wien

Burgtheater, Wien

Klimt Drawing, Burgtheater, Wien

Klimt Drawing, Burgtheater, Wien

The great art museum Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna celebrated Klimt with another raised platform, granting viewers a close look to Klimt murals dressed in their most splendid colors. The theme was aptly called "Face to Face with Gustav Klimt". His figures, confined in the niches, were quite like late medieval to early Renaissance paintings, stylized, otherworldly and absolutely enchanting. They bore less obvious hallmark of Klimt we generally attributed to him - free-flowing sumptuousness. Here, they were tightly controlled. Very classical.

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wien

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wien

Face to Face with Gustav Klimt, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wien

Face to Face with Gustav Klimt, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wien

Face to Face with Gustav Klimt, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wien

Face to Face with Gustav Klimt, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wien

Klimt's more signature paintings could be seen in two museums specializing in Austrian arts:

Oberes Belvedere (Upper Belvedere) and

Leopold Museum. These two museums, particularly Leopold, also boasted a stunning collection of Egon Schiele.

Oberes Belvedere and Fountain, Wien

Oberes Belvedere and Fountain, Wien

Oberes Belvedere and Fountain, Wien

Oberes Belvedere and Fountain, Wien

Klimt's paintings in Oberes Belvedere bore all the familiar traits of his; even his landscape had an unfettered sensuality, which was the hallmark of its epoch of self-expression and self-indulgence, of Freud.

Allee im Park vor Schloß Kammer, Gustav Klimt, um 1902, Oberes Belvedere, Wien

Allee im Park vor Schloß Kammer, Gustav Klimt, um 1902, Oberes Belvedere, Wien

His figure, particularly those female nudes, such as Eve (Eva) and Judith below, seemed live in the time and space utterly outside the domain implied by their respective titles. They were confident, seductive and overtly sensual. The juxtaposition of endless arrays of colors and patterns were dazzling. However, the overwhelming compote induced a sensation verging at nauseating.

Adam und Eve, Gustav Klimt, 1917-18, Oberes Belvedere, Wien

Adam und Eve, Gustav Klimt, 1917-18, Oberes Belvedere, Wien

Braut, Gustav Klimt, 1918, Oberes Belvedere, Wien

Braut, Gustav Klimt, 1918, Oberes Belvedere, Wien

Judith, Gustav Klimt,

1901,

Oberes Belvedere, Wien |

|

Wasserschlangen, Gustav Klimt,

1904-07,

Oberes Belvedere, Wien (public domain) |

|

|

Kuss, Gustav Klimt, 1907-08, Oberes Belvedere, Wien

Kuss, Gustav Klimt, 1907-08, Oberes Belvedere, Wien

After Klimt, the symbol of sumptuousness and sensuality of Fin de siècle and Viennese Secession, Egon Schiele's paintings of expressionism school, collected by the same Oberes Belvedere, Wien, were nitty-gritty reality, viewed through a personal lens, with a man whose creative height coincided with the brutal World War I. Even his quite becalming landscapes and townscapes had an unsettled feeling, and later in years, such as his 1917

Vier Bäume, a color scheme reminding viewers of bloodshed, despite and because of its undeniably beauty and certain nauseatingly sweetness.

Fensterwand (Hauswand), Egon Schiele, 1914, Oberes Belvedere, Wien

Fensterwand (Hauswand), Egon Schiele, 1914, Oberes Belvedere, Wien

Vier Bäume, Egon Schiele, 1917, Oberes Belvedere, Wien

Vier Bäume, Egon Schiele, 1917, Oberes Belvedere, Wien

Move on to his figure paintings, one was flooded by the survey of resigned hopelessness, yearning desire for life and love in adversary, and utter despair. Here were the manifests of tragedy of human race.

Mutter mit zwei Kindern III (Mutter III), Egon Schiele, 1915-17, Oberes Belvedere, Wien

Mutter mit zwei Kindern III (Mutter III), Egon Schiele, 1915-17, Oberes Belvedere, Wien

Familie (Kauerndes Menschenpaar), Egon Schiele, 1918, Oberes Belvedere, Wien

Familie (Kauerndes Menschenpaar), Egon Schiele, 1918, Oberes Belvedere, Wien

Tod und Mädchen, Egon Schiele, 1915, Oberes Belvedere, Wien

Tod und Mädchen, Egon Schiele, 1915, Oberes Belvedere, Wien

Umarmung (Liebespaar II, Mann und Frau), Egon Schiele, 1917, Oberes Belvedere, Wien

Umarmung (Liebespaar II, Mann und Frau), Egon Schiele, 1917, Oberes Belvedere, Wien

Astonishingly, Leopold Museum provided even more comprehensive survey of Egon Schiele, along with a few canvases of Gustav Klimt.

Leopold Museu, Wien

Leopold Museu, Wien

Leopold Museu, Wien

Leopold Museu, Wien

The Klimt paintings in Leopold were early works, in the realism tradition, though not without the keen psychological observation in its portraits.

Gustav Klimt, Leopold Museum, Wien

Gustav Klimt, Leopold Museum, Wien

Gustav Klimt, Leopold Museum, Wien

Gustav Klimt, Leopold Museum, Wien

Leopold Museum did have one of his later works, a masterpiece,

Tod und Leben (Death and Life), which seemed combined the outlandish surface beauty of his own, and the depressing pessimism from his younger peer, Egon Schiele.

Tod und Leben, 1910, Gustav Klimt, Leopold Museum, Wien

Tod und Leben, 1910, Gustav Klimt, Leopold Museum, Wien

However, no one could outdo Egon Schiele in the province of unmitigable sadness and despair, demonstrated by his seemingly innocent landscapes and townscapes, seductive femme fatales, and the most wrenching group portraits. He became my new hero, who had an unflinching look at misery and death.

Speaking of death, a sad note was that both Klimt and Schiele died in 1918, of the great influenza after World War I. Death had never been far away from frivolity.

Leopold Museum, Wien

Leopold Museum, Wien

Egon Schiele, Leopold Museum, Wien

Egon Schiele, Leopold Museum, Wien

Der Häuserbogen II (,,Inselstadt''), 1915, Schiele, Leopold Museum

Der Häuserbogen II (,,Inselstadt''), 1915, Schiele, Leopold Museum

Kalvarienberg, 1912, Egon Schiele, Leopold Museum

Kalvarienberg, 1912, Egon Schiele, Leopold Museum

Versinkende Sonne, Egon Schiele, Leopold Museum

Versinkende Sonne, Egon Schiele, Leopold Museum

,,Rabenlandschaft'', 1911, Schiele, Wien 1900, Leopold Museum

,,Rabenlandschaft'', 1911, Schiele, Wien 1900, Leopold Museum

Die Kleine Stadt II, 1912-13, Schiele, Wien 1900, Leopold Museum

Die Kleine Stadt II, 1912-13, Schiele, Wien 1900, Leopold Museum

Bildnis Wally Neuzil, 1912, Egon Schiele, Leopold Museum, Wien

Bildnis Wally Neuzil, 1912, Egon Schiele, Leopold Museum, Wien

Bildnis Wally Neuzil, 1912, Egon Schiele, Leopold Museum, Wien

Bildnis Wally Neuzil, 1912, Egon Schiele, Leopold Museum, Wien

Trauernde Frau, 1912, Egon Schiele, Leopold Museum

Trauernde Frau, 1912, Egon Schiele, Leopold Museum

Sitzender Männerakt (Selbstdarstellung), 1910, Egon Schiele, Leopold Museum, Wien

Sitzender Männerakt (Selbstdarstellung), 1910, Egon Schiele, Leopold Museum, Wien

,,Die Eremiten'', 1912, Egon Schiele, Leopold Mueum, Wien

,,Die Eremiten'', 1912, Egon Schiele, Leopold Mueum, Wien

Rückenansicht eines weiblichen Halbaktes mit Tuch (Fragment), 1913, Schiele

Rückenansicht eines weiblichen Halbaktes mit Tuch (Fragment), 1913, Schiele

Rückenansicht eines weiblichen Halbaktes mit Tuch (Fragment) (details), 1913, Schiele

Rückenansicht eines weiblichen Halbaktes mit Tuch (Fragment) (details), 1913, Schiele

Blinde Mutter, 1914, Egon Schiele, Leopold Museum

Blinde Mutter, 1914, Egon Schiele, Leopold Museum

Egon Schiele, Leopold Museum

Egon Schiele, Leopold Museum

Mutter mit zwei Kindern II, 1915, Egon Schiele, Leopold Museum

Mutter mit zwei Kindern II, 1915, Egon Schiele, Leopold Museum

Drei stehende Frauen (Fragment), 1918, Egon Schiele, Leopold Museum

Drei stehende Frauen (Fragment), 1918, Egon Schiele, Leopold Museum

Kardinal und Nonne, Egon Schiele, Leopold Museum

Kardinal und Nonne, Egon Schiele, Leopold Museum

Liebssatt, 1915, Egon Schiele, Wien 1900, Leopold Museum

Liebssatt, 1915, Egon Schiele, Wien 1900, Leopold Museum

Related posts on

Art · 文化 · Kunst:

- Magnificent Churches in Vienna

-

Naked Audience for Naked Men Exhibit at Leopold Museum, Vienna

-

Angelic and Evil - Bunkerei and Palais Augarten in Augarten, Vienna

Label:

Austria,

Austria and Italy Trip 2012

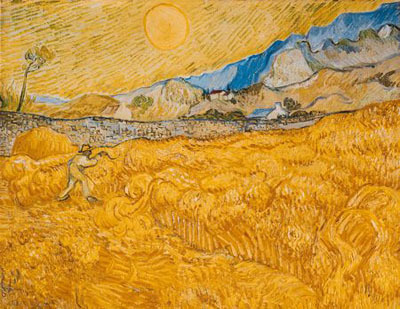

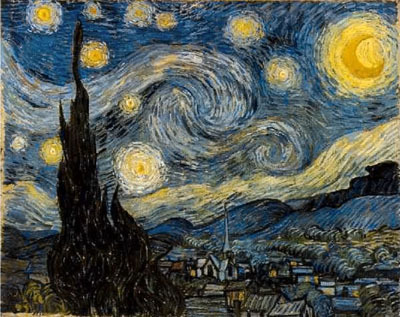

Yesterday, 30 December 2012, I returned to De Young Museum in San Francisco for The William S. Paley Collection: A Taste for Modernism, on the very last day of the exhibit, of which The De Young Museum website informed us was "A selection of major works from the William S. Paley Collection at the

Museum of Modern Art in New York.. A pioneering figure in the modern entertainment,

communication and news industries, Mr. Paley (1901–1990) was a founder

of the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS), and a dedicated

philanthropist and patron of the arts. The Paley Collection, which

includes paintings, sculpture and drawings, ranges in date from the late

19th century through the early 1970s. Particularly strong in French

Post-Impressionism and Modernism, the collection includes multiple works

by Paul Cezanne, Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso, as well as

significant works by Edgar Degas, Henri Toulouse-Lautrec, Paul Gauguin,

Andre Derain, Georges Rouault and artists of the Nabis School such as

Pierre Bonnard and Edouard Vuillard."

Yesterday, 30 December 2012, I returned to De Young Museum in San Francisco for The William S. Paley Collection: A Taste for Modernism, on the very last day of the exhibit, of which The De Young Museum website informed us was "A selection of major works from the William S. Paley Collection at the

Museum of Modern Art in New York.. A pioneering figure in the modern entertainment,

communication and news industries, Mr. Paley (1901–1990) was a founder

of the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS), and a dedicated

philanthropist and patron of the arts. The Paley Collection, which

includes paintings, sculpture and drawings, ranges in date from the late

19th century through the early 1970s. Particularly strong in French

Post-Impressionism and Modernism, the collection includes multiple works

by Paul Cezanne, Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso, as well as

significant works by Edgar Degas, Henri Toulouse-Lautrec, Paul Gauguin,

Andre Derain, Georges Rouault and artists of the Nabis School such as

Pierre Bonnard and Edouard Vuillard."