The Smell

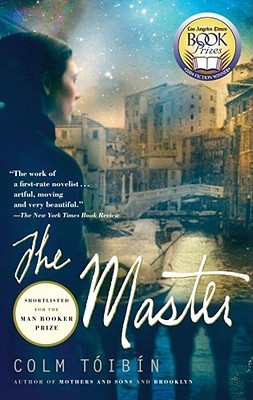

Recently, I read a much lauded novel, The Master, by Colm Tóibín, based on the life of the famous American writer, Henry James; the novel attempted to capture the man, his time, and the creative process, tracing James’s paths from America to France, Italy, and the UK.

The book, a variation on the theme of isolation, detachment, loneliness, and creativity, felt rather prosaic, especially in the episodes dealing with creative process, when life experiences grant James instantaneous inspiration, a process not unlike painting by numbers: simplistic and mechanical. That said, there were some very vivid passages, with the most affecting one depicting Henry James inhaling the foul smell of his brother’s discarded Civil War uniforms:

Wilky came home with no belongings. Even his uniform was rotting and had to be carefully removed. The blanket that covered him was thrown aside and left in a corner of the hallway. It was a few days before Henry, doing vigil over his brother, noticed it and carried it to the kitchen. As he unfolded it there, the smell was overwhelming, but so fiercely redolent of Wilky's suffering in the battlefield that he could not easily cast it aside. It smelled of tobacco, and it smelled of the strange mixture of rot and human sweat which Wilky's uniform had reeked of. But more than anything, it smelled of the earth itself, the earth of mud and muck and of war, the earth which had been stormed by regiments and disturbed by grave diggers, the fetid earth. He found a place for the blanket in a shed behind the kitchen and went back to the hallway, but the smell remained with him. It was the most vivid testament to what his brother had been through.This episode struck a special chord in me, as the passage was almost a replay of a watershed moment in my life that took place twenty-five years ago, in 1989.

[pages 176-177, Scribner paperback]

Year of Trouble

That year, 1989, was the year of Loma Prieta earthquake in San Francisco; the year of the Fall of the Berlin Wall; the year Czechoslovakia’s Velvet Revolution; the year Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini died; and the year of the dethroning and execution of Romanian Communist leader Nicolae Ceauşescu and his wife Elena. To Chinese people with persistent memories, and to all the rest of the world, 1989 was also the year of the Tian'anmen Square (or Tiananmen Square) protests that began in mid-April and reached its climax in the Massacre in the suburban roads leading to the Square in Beijing during the early hours of the Fourth of June.

The event that triggered the mass protest amongst university students in Beijing was the death of a former leader, Hu Yaobang, who lost his Party Secretary General post when he was deemed too sympathetic to college students who protested in 1986-87, demanding greater personal, press, and political freedom.

During Lunar New Year winter break in early 1989, my father, a civil servant and a political survivor, warned me that the Communist Party, aka The Party in China, had been bracing itself for brooding troubles already, as 1989 was a year of many anniversaries, e.g. the fourth of May -- the 70th anniversary of the enlightenment movement, starting with students’ street protest in Beijing; and the 1st of October, the 40th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic.

These potentially celebratory milestones could easily cause mass protests, as the problems ignited the protests two years ago had only deepened, and graft and corruption became more rampant during the privatization process when assets that were formerly owned collectively were swallowed up by those with power and connections. The resentment permeated all strata of society, but was most acutely felt among more self-aware intellectuals, and particularly university students who faced the prospect of earning only a pittance after graduation, left far behind by hardworking laborers and vendors who could have accumulated a small fortune -- let alone the fabulously nouveau riche, with connections to power. Worse, the decade old job guarantee for university graduates was to be gradually repealed. The prevailing atmosphere in colleges was either sullen discontent or affected hedonism, unless one wanted to study English so as to study abroad post-graduation.

As a sophomore in a prestigious and rigorous science/engineering program at Dalian University of Technology, I planned to take the necessary TOEFL and GRE tests before graduation, in order to win a seat at an American graduate school. Though alert to politics, I chose to be oblivious of the events in Beijing when trouble started to brew in mid-April.

However, I couldn’t ignore it for long. On the 26th of April, an editorial was published by People's Daily, a newspaper traditionally entrusted by the party to send signals of major campaigns. The editorial condemned students protestors for causing disturbances and being used by evil social elements, and made ominous threats to the disobedients. People were required to "study" the editorial and I too, however furious I felt, added my voice to the collective condemnation of the troublemakers in several “study sessions.” I expected this would be the end of the protests in Beijing.

I was wrong. Beijing students made a righteous demand that the incendiary editorial be retracted. A protracted tussle over its retraction propelled more and more students in Beijing, and gradually students from the provinces, into the streets; the government would not yield and by the end of April, the situation came to an impasse.

The major holiday May Day saw the first protest march in Dalian but I stayed away, so as to entertain a visiting friend. On a beach, my friend and I were chastised by several old women for not marching with other students, protesting against the "stubborn and corrupt government".

On the Fourth of May, the designated Chinese Youth Day, young students from many cities, particularly from coastal regions, staged major marches in responding to their peers in Beijing, whose voices echoed those heard 70 years before. I took part in my first protest march, willfully believing it a grand finale.

On the evening of 13 May, my two roommates came back from network TV news and pantomimed the postures and attire of some Beijing students who had gone on hunger strikes, with the stirring headbands written with slogans in black or red ink: exciting, alarming, and distasteful. The hunger strike was timed to take place two days prior to the highly publicized state visit by Mikhail Gorbachev, for maximum exposure in the press. Gorbachev came and went without meeting the students, who had in vain hoped for a Chinese Gorbachev.

Since the hunger strike started, students in my university had stopped going to classes. Professors and lecturers would not dare to strike, but they could gleefully tell the handful who showed up, either timid people or students who wanted to demonstrate their steadfast loyalty to the Party, that the classes could not take place due to insufficient number of students present.

Beijing Bound

17 May, in the late afternoon, our campus became more agitated and my best friend, Sam (using names adopted in English class for convenience), came to borrow money for train ticket to Beijing - many people wanted to go to Beijing to witness the "historical event" and show their support, that very evening. I was flummoxed but soon made the decision to join him. Cindy, one of the handful of female students in our program, and the third party of our carefully balanced ménage à trois then declared her resolution to go with me. The father of one of Sam’s local roommates came to warn us of the ruthlessness of Deng Xiaoping but we paid no heed to him. Because we ourselves didn’t believe in any real danger, we couldn’t persuade Cindy to stay. So I followed Sam and Cindy followed me: the start of our impulsive adventure.

Before we left, the Chair of our department, and other administrators too, visited our dorms to entreat us not to go; failing that, our Chair begged us to take good care of ourselves and each other, to be safe, and to return as soon as we had voiced our support to the hunger strikers. By then all six of my roommates had decided to go to Beijing. Two of them, who had actively sought party membership in the past, and sounded most sincere in denouncing the “disturbance” caused by protesting Beijing students, surprised us by joining us. Another roommate had chanced upon their side meeting with our life advisor (similar to a homeroom teacher) and warned me not to say too much in front of those dubious two.

Our university officials arranged to have a fleet of school buses to drive us to the train station - a measure that probably cost the decision maker(s) some trouble later on, though I did not hear of any consequences. By dinner time, we boarded the buses for Beijing, and about an hour later we arrived from our suburban campus to downtown Dalian. Our school buses negotiated streets teeming with protesters from many universities, who called out that we should join them; but once they learned our purpose and destination, paths were cleared and spontaneous cheers trailed behind us.

We received tickets from our organizers, who bought them collectively. None of us had seat reservations, and the already-crowded train became packed once we entered cars randomly chosen by more than a thousand of us. Despite the possibility of standing for the entire 18 hour journey, we were in rather good spirits. Neither Cindy nor Sam had ever been to Beijing, and were excited to visit the capital. Cindy, especially, eagerly solicited advice on places to visit, from everyone around us, endearingly and annoyingly. A boy from my neighboring dorm room climbed onto the luggage rack and started to write to his girlfriend, one of Cindy’s roommates, who was too sensible to come with us. Cindy's best friend and roommate Helen was with us in order to see her high school boyfriend, who was studying in a Beijing university.

After some hours, we managed to secure several seats for our small group. We took turns sitting, or squeezed together on too-few seats, for the rest of the journey, sharing the little food we brought with and could afford to purchase from the train's staff.

The next day, 18 May, we grew more exhausted but our spirits dampened little. We sang to ourselves and cheered to passing trains. During an unexpected, long delay we waved most cheerfully toward long columns of freight trains on the other tracks, full of uniformed soldiers and heavy weaponry. They were as young as we were, perhaps younger, and more innocent: less educated and privileged. We felt instant connection and compassion. We magnanimously waved on, taking no heed whether they waved back or not.

In Tianjin, an hour or so from Beijing, many noisy students boarded, but pointedly ignored us. We were somewhat hurt by the sense that we were uninvited guests to an exclusive party. Near the end of the day, we entered Beijing and the the locals, realizing the distance we'd covered from the banners we carried, gave us huge cheers and that tempered a bit of our resentment toward those who “owned” the movement. Finally, we arrived in the surprisingly quiet Beijing Train Station. Some organizers made brief headcounts and led us on a march through the Chang'an Avenue, a thoroughfare between the train station and Tian'anmen Square, the center of the protest. On our way to the Square, we were buoyed to learn that on 17 and 18 May, one million people marched in the city each day. Our pride at participating in the historic One Million March could have borne us aloft if our bodies hadn’t been so abused and dead heavy.

In Tian’anmen Square

The atmosphere at Tian'anmen Square was nothing but cheerful. The vast square was filled with people, and it was completely cordoned off with checkpoints to maintain order: to allow easy access for medical personnel, ambulances, and student protesters; and to prevent government agents or extremist agitators from hijacking the process and agenda.

|

| Revisiting the camping spot, which was off limit in 2005 |

Almost as soon as we marked out our camping site on the scorching bare ground, a huge downpour surprised us. By the time plastic sheets were distributed to us, we were nearly soaked through, though we were dried again almost as soon as the rain stopped due to the unseasonal heat.

Early evening saw Beijing citizens delivered incredible quantities of warm food in all kinds of vehicles and we got plenty of what we needed. It must be a huge challenge to feed all those people, and provide necessary toilets. I only remember the food -- not the toilets; therefore, I deduce that they must have been clean and decent enough not to have left an impression.

After night fell I started to take in the hubbub surrounding us -- milling people, distant sirens and slogan-shouting, etc. When Helen left us to search for the camp of her boyfriend, the rest of us decided to take a break and perhaps to find some famed Beijing snacks in the neighborhood, instead of trying to visit Mao’s mausoleum as proposed by one boy who hailed from the cradle of the Communist revolution and held Mao dearer than most.

We circled around the immediate environs of the Square and did find a couple snack vendors selling crepe-like snacks. Afterward, we turned back from the orderly but rather deserted city. Despite the apparent peacefulness of the streets, the contrast within and without the Square was so huge and disquieting that we abandoned our plans to visit the night market in the city’s commercial center, or to try out the subway for the first time visitors to Beijing. By the time we returned, the Square had become eerily quiet except for loudspeakers from the outskirts of the Square, still audible though weakly, telegraphing a mixture of checked anxiety and surreal calmness. The sound was like lulling ocean waves, accompanied by bright lights at the edges of the Square seeping into the vast expanse, rendering it just bright enough not to be pitch black and terrifying. The sound eased us toward sleep, though I was momentarily anxious for lurking danger -- after all, we were bedded down in the very same spot where Mao Zedong’s militias savagely attacked peacefully protesting people in 1976.

We slept on the hard stone pavement, with our traveling bags as pillows, and pressed against each other for warmth. Though it was very hot during the day, it was quite cool if not chilly at night. Cindy had a severe headache and cried out for her mommy, and I was feverish as well. Our careless adventure was turning out to be a trial.

The next morning, 19 May, we got up late and didn’t bother to try to see the national flag ceremony in front of Tian’anmen -- The Gate of Eternal Peace -- as proposed by some. The Square was hot again as soon as the sun rose, and people started to go out to march. It seemed to be just another normal protesting day. Yet, later, we realized that it was a fateful day -- at dawn, the Secretary General of the Communist Party, Zhao Ziyang, who opposed cracking down on the protest, had lost power to hardliners, and paid a defiant visit to some students at the camp to bid them farewell.

We were too overwhelmed by our surroundings to stray. We did not even go the the north edge of the Square to see the famous gate, Tian’anmen. With many people having left the Square for various reasons, I saw more of the open space, which was covered with scattered bags, books, newspapers, flyers, hats, shoes, etc. amongst the sprawling bodies. All the scattered objects were still but I could practically see illness festering in them, ready to pounce. People slumbered here and there, facing up, sun-burned, or facing down, like corpses floating on a gray ocean. All day long, fully masked medical staff walked around to spread disinfectant out of huge tanks on their backs and other medical staff made their rounds to inspect, consult, and distribute medicines.

By mid afternoon, a certain message mysteriously materialized and was passed along in hushed tones: the government might make a move, and students from provinces must vacate today and leave the further struggle to the better equipped and prepared students from Beijing and nearby, e.g. Tianjin. We came, we supported, we voiced our opinions and now we ought to leave. The unknown origin of the message and its assertive tone carried an irrefutable weight, and our physical and mental exhaustion and confusion decided for us: we would leave.

Retreat and the aftermath

By evening, the majority of students from our university assembled again, in smaller and scattered groupings, to return to Dalian. Every one of us had became slightly unhinged by the heat and anxiety, either hollow-eyed or dazed. Just as our anxiety peaked and Cindy became almost hysterical, Helen came back in tears. She had found her boyfriend, who was fasting in one of the hunger-strikers' tents ... together with his new girlfriend! Helen nursed them together for the whole day till her spirit was ready to crumple. When we arrived at train station, like retreating soldiers, we were allowed to enter and to get on board without tickets. The authorities were anxious to get people out of Beijing, perhaps, or the railroad staff were extremely sympathetic to us.

Next morning, 20 May, we woke up to the news broadcast over the train’s PA system. In dead silence we listened along with other stunned and sullen passengers to an announcement that the government had declared martial law in part of Beijing! Still, I failed to connect the declaration of martial law to those soldiers I saw two days earlier on the freight trains on adjacent tracks to ours. Only when the massacre took place two weeks later did the pieces fit together. My imagination and understanding had failed to account for the government’s brutality.

Next morning, 20 May, we woke up to the news broadcast over the train’s PA system. In dead silence we listened along with other stunned and sullen passengers to an announcement that the government had declared martial law in part of Beijing! Still, I failed to connect the declaration of martial law to those soldiers I saw two days earlier on the freight trains on adjacent tracks to ours. Only when the massacre took place two weeks later did the pieces fit together. My imagination and understanding had failed to account for the government’s brutality.When we journeyed back to school, the first thing we did was to rush to the communal bathhouse for a cleansing hot shower. Only when I washed and changed did I realize how unbearably foul my dirty, reeking clothes had become -- like the strange mixture of rot and human sweat of Wilky’s uniform as Colm Tóibín described it. I felt so bad for fellow travelers who had to suffer our filth in the train and bus. Perhaps, knowing that we were struggling for all Chinese people, they bore our collective stink with great fortitude.

Two of my six roommates chose to remain in Beijing. We worried a great deal about them, before, during, and after the massacre. Only about a week after the bloodletting in Beijing did we learn they had come home safely.

There were many consequences in the aftermath of the protests and massacre, some immediate and others more distant, some personal and others indirect. At one time, I was quite convinced that I would never be able to finish my university education. Yet all four of us -- Cindy, Helen, Sam and I -- continued to fight tooth and nail to escape that corrupt country whose government slaughtered our peers. But those stories are for another time.

Our adventure to Beijing was a bit foolhardy, sophomoric, and selfish: romantic rather than heroic. I had difficulty thinking about, let alone talking about the journey. The toil, and our pollution by the time we returned, brought me more shame than pride. The passage about Wilky’s Civil War uniform in Colm Tóibín’s The Master vividly recalled to memory those post-Tian'anmen smells, the smells I had managed to repress in my memory, though I have never lost the sinking realization of how befouled we had become on our journey to the heart of China’s 1989 protests. I shall not ever forget that, nor, now that Tóibín has reawakened the sensation, the smell itself.

Related posts on Art · 文化 · Kunst:

- Bloody June Fourth (六四) in Beijing, 23 Years Later

- Confucius Statue in Tiananmen Square- Tunisia, Egypt... Who's Next?

- What Chinese People's Daily Reported on Libya Crises

- The Ghost of Mao Zedong

- Facebook in China

- Where Is Ai Weiwei

- Censorship, and Behind the Kitchen Door

- Most Fortunate Chinese - Beijing Residents, on Drought and Water Project in China

- Three Gorges Dam and Anti-Rightists Campaign in China

- "Liberation Road" Completed

- My Hero Käthe Schmidt Kollwitz (July 8, 1867 – April 22, 1945)

- My "Apocalypse Series" on Synchronized Chaos Webzine

- Mao's Last Dancer?

No comments:

Post a Comment